Resource handling and move semantics

Techniques to automatically manage the run-time lifetime of resources include reference counting, where multiple references to the same resource exist, and ownership transfer where only a single reference to a resource at any given time does exist.

The two approaches result in a completely different set of implementation challenges:

- Shared ownership: reference cycles (two objects pointing at each other) and serialized access to the reference counter and possibly the resource itself (through e.g. overloading of the -> operator)

- Single ownership: copy construction from a source object and reset of the resource reference in the source object itself to avoid multiple destruction attempts

This post describes a possible implementation, in both C++98 and C++11 language

standards, for a resource handler with ownership transfer similar to

auto_ptr/unique_ptr to be used for resources such as file descriptors/streams,

sockets and memory pointers.

Glossary

- resource

-

any entity that follows a create-use-dispose run-time usage pattern

- handle

-

the actual resource identifier: memory pointers, file and socket descriptors, OpenGL resources, OpenCL memory objects…

- handler

-

the class wrapping resource handles

A minimal resource handler

A minimal resource handling class shall accept a resource identifier in its constructor and destroy it in the destructor. E.g.

template <typename T>

class MemoryHandler {

public:

//explicit: no automatic conversions

explicit MemoryHandler(T* ptr) : ptr_(ptr) {}

T* ptr() { return ptr_; }

~MemoryHandler() { delete ptr_; }

private:

T* ptr_;

};

This class can already be used to perform simple scope-based resource management: the resource is deleted when the handler goes out of scope.

void PrintCppStd() {

MemoryHandler< Printer > mh(new Printer("remote printer 1"));

Printer* p = mh.ptr();

p->Print("./ISO_IEC_14882-2011.pdf");

} //resource automatically destroyed by MemoryHandler destructor upon exit

The resource is destroyed by the Printer destructor when the instance goes out

of scope, this means that there must be only a single instance of MemoryHandler

pointing to the Printer instance, if multiple instances of MemoryHandler

pointing to the same Printer instance exist they will all try to delete the

same resource resulting in a run-time error when the destructors get invoked.

In order to enforce the single ownership requirement we need to transfer the ownership, i.e. the responsibility to manage the resource lifetime, from one object to another upon construction and copy operations.

The object owning a valid resource handle is the one that shall dispose the resource when its destructor is invoked.

To implement ownership transfer we can start by adding a copy constructor and assignment operator accepting a non-constant reference to another reference handler which copies the pointer and resets the pointer in the source object:

MemoryHandler(MemoryHandler& mh) : ptr_(mh.ptr_) {

mh.ptr_ = 0;

}

A copy constructor accepting a non-constant reference can however only be used to copy from non-temporary objects and will not work with objects returned from functions.

Ownership transfer

In order to have ownership transfer work with temporary source objects we need to implement a proper copy constructor and assignment operator.

Note that assignment and construction must not only copy the resource pointer but also notify the source object that it has lost ownership of the resource and must not try to dispose it.

One way to notify the source object of lost ownership is to simply reset its

inner ptr_ resource handle to an empty or invalid value, i.e. to 0 or

nullptr in the case of a memory pointer.

The copy constructor accepting a non-constant reference is useful to prevent moving constant resource handlers but we also need to have a constructor that allows to construct a new object from a temporary object.

Move semantics

Move semantics refers to the act of moving the content of an object into another object without performing explicit copies.

Move semantics is in fact implemented in terms of ownership transfer as a copy and reset operation applied to resource handles.

A typical case where move semantics is useful is copying from a temporary

object (e.g. returned from a function) that contains a heap allocated pointer

as a member variable: since the allocated memory is going to be released after

the copy, instead of performing allocate-copy-free operations it is much faster

to simply copy the pointer into the new object and reset the pointer of the

temporary source object to nullptr so that memory is not released when the

temporary object goes out of scope.

A typical case where move semantics is required is storing resource handlers requiring single ownership (e.g. sockets or C++ 11 threads) into standard library containers.

When adding an element to e.g. an std::vector the element has to have its

internal handle moved to the object stored into the container.

Note however that it might not be a good idea to store resource handlers into containers unless you are 100% sure that no additional hidden copies happen internally during the common container operations.

It might indeed be a better idea to store the actual resource handles in the container and have the resource handler wrap a heap allocated container filled with handles.

Adding move semantics

The current MemoryHandler implementation can only be used to perform scope-based automatic resource management.

To fully support move semantics we need:

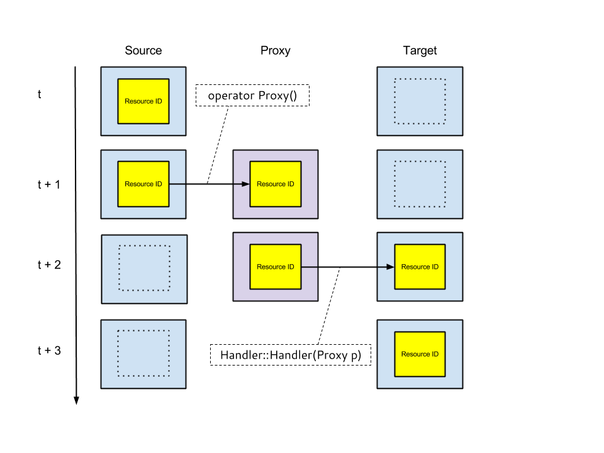

a move constructor to move data from temporary objects (e.g. returned from functions) into a newly constructed object an assignment operator that can move resource handles from the r-value to the l-value instance One way of supporting construction and assignment from temporary objects is to create a new type that wraps the inner resource handle and add a conversion operator and move constructor accepting instances of this new type.

The copy-through-proxy and reset technique is known as the Colvin and Gibbons trick.

The Proxy type is implemented as an inner class, no need for visibility from the outside:

template class MemoryHandler {

private:

struct Proxy {

T* ptr;

};

...

Conversion operator, constructor and assignment:

operator Proxy() {

T* ptr = ptr_;

Proxy p;

p.ptr = ptr;

ptr_ = 0; //memory handler has moved out: reset this->ptr_

return p;

}

MemoryHandler(const Proxy& p) : ptr_(p.ptr) {}

MemoryHandler& operator=(MemoryHandler& mh) {

MemoryHandler(mh).Swap(*this);

return *this;

}

private: //helper swap method

void Swap(MemoryHandler& mh) {

std::swap(mh.ptr_, ptr_);

}

Limitations

As it stands we have a class that:

-

properly manages the lifetime of a memory buffer identified by a memory handle (pointer)

-

supports construction and assignment from non-const and temporary objects

-

prevents constant objects from being moved

Now let’s see what happens if you try to store an instance of MemoryHandler

into a standard container such as std::vector:

std::vector< MemoryHandler< int > > mhandlers1;

mhandlers1.push_back(MemoryHandler< int >(new int(1)));

std::vector< MemoryHandler< int > > mhandlers2(1);

MemoryHandler< int > mh(new int(1));

mhandlers2[0] = mh;

When compiling with clang++ the first reported error is:

error: no matching constructor for initialization of 'MemoryHandler'

{ ::new(__p) _Tp(__val); }

^ ~~

this is because there is no copy constructor available which accepts a constant reference.

Alternative ways to implement move semantics do exist e.g. add a mutable guard

data member that is set to false when the object loses ownership of the

resource handle and avoids destroying the resource if the object does not own

it. The problem with this approach is that it allows to move any const object

preventing the implementation of e.g. the

safe auto_ptr idiom

Move semantics and standard containers

In cases where all the objects in the container must be destroyed together at the same time, instead of storing resource handlers as elements in standard containers you can simply wrap a container instance with a resource handler store the actual resource handle (e.g. a memory pointer) inside the container the handler’s destructor will take care of iterating over the container and release every resource one by one.

In cases where resource handlers can be inserted and removed into/from the container: use the approach described above and

wrap elements with resource handlers when removed from the container extract resource handles from handlers when adding resources to the container The only addition to the MemoryHandler class required to make this strategy work is a release() method which resets the internal pointer to 0 and returns the previously stored pointer.

The code to manage a set of handles within a container then looks like:

//create a handler wrapping a heap allocated standard container

MemoryHandler< std::vector< int* > > handler(new std::vector< int* >);

std::vector<int*>& handles = *handler.ptr();

MemoryHandler mhIn(CreateHandler(...));

....

//store the pointer into the collection and set the internal pointer

//to zero inside the memory handler

handles.push_back(mhIn.release());

...

//extract a pointer from the container; will not reset the pointer

//inside the container, so you end up with two pointers referencing

//the same memory location

MemoryHandler mhOut(handles.front());

//manually reset the pointer in the container:

handles.front() = 0; //moved; need to do this automatically

To perform the resource extraction and automatically reset the source handle in one call you can use a simple release function:

template < typename T >

T* release(T*& rh) {

T* ret = rh;

rh = 0;

return ret;

}

The code to perform the actual resource extraction and reset then becomes:

MemoryHandler< int > mhOut(reset(handles.front()));

without the need to explicitly set the std::vector element to zero.

Whether you decide to physically remove the element from the vector or not it is not a problem since it will not cause any error upon destruction of the container.

C++ 11

If you can use a C++ 11 conformant-enough compiler such as:

- gcc >= 4.8

- clang llvm >= 3.2

- Intel icc >= 14.0

- PGI >= 13.1

- Microsoft VS >= 2012

you can avoid tricks and hacks and simply use r-value references to perform the move.

Here is the same MemoryHandler class implemented with r-value references and

calls to std::move when needed.

template < typename T >

class MemoryHandler {

private:

struct Proxy {

T* ptr;

};

public:

MemoryHandler(MemoryHandler&& mh) : ptr_(mh.ptr_) {

mh.ptr_ = 0;

}

MemoryHandler(const MemoryHandler&) = delete;

explicit MemoryHandler(T* ptr = 0) : ptr_(ptr) {}

T* ptr() { return ptr_; }

~MemoryHandler() {

delete ptr_; //it is fine to call 'delete 0'

}

MemoryHandler& operator=(MemoryHandler&& mh) {

MemoryHandler(mh).Swap(*this);

return *this;

}

MemoryHandler& operator=(const MemoryHandler& mh) = delete;

private:

void Swap(MemoryHandler& mh) {

std::swap(mh.ptr_, ptr_);

}

private:

T* ptr_;

};

If you are however stuck with compilers like Open64, Cray or NVIDIA nvcc you will need to use the various strategies outlined in the previous sections for the foreseeable future.

One more thing…

Automatic resource management techniques can be applied to types other than

memory pointers, in my case I use sockets (regular and zmq), threads, OpenCL

memory objects, CUDA and OpenGL resources; it is however always possible to

use versions of the MemoryHandler implemented in this article by simply

wrapping the resource handles with a heap allocated instance of a wrapper

class. e.g.

class Socket {

public:

Socket(int s) : socket_(s) {}

int get() { return socket_; }

~Socket() { close(socket_); }

private:

int socket_;

};

...

MemoryHandler< Socket >

sh(new Socket(socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP)));

int aSocket = sh.ptr()->get();

If you want to avoid memory management operations you can always define a generic Handler class using policy based design, you’ll need policies for:

validation: to detect if a resource can be safely disposed setting an

empty/invalid value: to signal the wapper object it has lost ownership of the

resource and must not try to dispose it releasing the resource: to dispose the

resoure upon destruction of the resource handler instance Note that you usually

do need an implementation of policy-based design or strategy pattern to properly

dipose the resource through a release function provided by client code to the

handler class; one example is the case of arrays: a delete [] operator has to be

invoked instead of delete.

A reworked version of the MemoryHandler class is shown below (C++11 version only).

template <typename T,

typename ValidationPolicy,

typename ResetPolicy,

typename ReleasePolicy>

class Handler {

public:

Handler(Handler&& h) : res_(h.res_) {

ReleasePolicy::Reset(h.res_);

}

Handler(const Handler&) = delete;

explicit Handler(T res = T()) : res_(res) {

ReleasePolicy::Reset(res_);

}

T& get() { return res_; }

const T& get() const { return res_; }

~Handler() {

if(ValidationPolicy::Valid(res_)) {

ReleasePolicy::Release(res_);

}

}

//Handler(Handler&&) automatically invoked if needed

Handler& operator=(Handler h) {

h.Swap(*this);

return *this;

}

Handler& operator=(const Handler&) = delete;

private:

void Swap(Handler& h) {

std::swap(h.res_, res_);

}

private:

T res_;

};

C++11 standard collections do support move semantics out of the box through

r-value references, it is therefore possible to move objects into collections

through the std::move function.